![]()

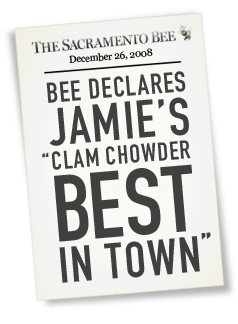

The Sacramento Bee, 1/10/2007

Jamie's joint - Out of the way

but also out of the ordinary,

Jamie's Bar & Grill thrives by

not changing

In a restaurant world nourished by teeny-weeny entrees, sometimes one big plate is better than a dozen small plates. Sometimes blue collar is better than white tablecloth. Sometimes dining dinosaurs endure and triumph.

Sometimes joints salted with the spirit of a buzz-cut, no-nonsense guy nicknamed "Big Jim" pay off.

Take the case of Jamie's Bar & Grill.

Jamie's, a boneyard of edible pleasure, is at 427 Broadway. This is lower Broadway. Any lower and you'd be in the Sacramento River. To get to Jamie's, you pass by a Target, the City Cemetery, the projects and an Asian grocery, where pinches of medicinal herbs are weighed with an ancient, hand-held scale.

But we digress. Or perhaps we're lost.

To get to Jamie's, just keep sight of the weirdly southwestern Channel 10 TV tower. Or follow the tasty smoke signals, which puff-puff-puff from the belly of Jamie's glowing, Rodinesque barbecue.

Before it was Jamie's, it was Shanley's Bar & Grill, operated by Bill Shanley, a garrulous publican from upstate New York. And before that, it was Medico's Saloon, operated by Medico Canische, surely one of more wondrously named, redoubtable Portuguese to ever hail from the city's once-scrappy south side.

Their legacies are still visible here. In fact, the place hasn't changed in, what, 30, 40 years?

Your hesitance to enter is understandable.

"Just the way the building looks," says Jamie Bunnell, owner-chef, who was born with a malted spoon in his mouth. "There are no windows. You can't drive by and look inside. If you didn't know any better, you might drive by and think it's a biker bar."

Please, let's not diminish Jamie's myriad charms. It looks worse than a biker bar. With its brown-shingled facade, its mansard of red Spanish tile, its Kelly green awning, its row of crooked wharf lamps, its adjacent, derelict Quonset hut, Jamie's looks like a clam shack turned into an Irish sweatshop.

But, right now, as the table is swept of crumbs from the year 2006, Jamie's is the toast of a much-beleaguered Broadway. Consider the RIPS: venerable Joe Marty's remains shut; wiseacre Eddie Fong is gone; Tower Records, impossibly, deceased. The boulevard has taken some blows.

Jamie's survives. No, offering value, a veteran staff, museum-quality surroundings and hefty, home-cooked portions, all prepared by Bunnell, who cooks super-size in an office cubicle, Jamie's thrives.

"I've been going there since it was Medico's," says Chuck Mier, who owns the estimable Club 2 Me, itself a legend on J Street. "It's just a wonderful, old-time spot."

Quality and size

On a rainy morning, well before the lunch hour, the potholes leading up to Jamie's are soup bowls. Inside, there's a worn plank floor, a long, shapely bar, beer signs and pub mirrors. A shaggy bison's head keeps baleful vigil in the compact dining room.

Jamie Bunnell, swathed in an apron, emerges from the kitchen, wiping his meaty paws on a white towel.

Bunnell is 48 years old. At 6-foot-2, 240 pounds, he's a big loaf of Wonder bread -- fleshy, pallid, with a shag of graying brown hair and dark circles under his otherwise keen, brown eyes. He has the pleased if fleeting half-grin of his father, whom everyone called either "J.B." or "Big Jim."

Modest, self-effacing, dry-humored, with a tender gait due to a rebuilt knee, Bunnell is completely without ill-will or pretense. All he knows is food and honesty. He sips muddy coffee from a glass pint.

His specials today include meatloaf, pork chops, diver scallops and opakapaka.

"I try to do something different every week," Bunnell says. "From pot roast to baked turkey to lamb shanks. We try to give people things they can't get elsewhere. Something hearty."

Something sizable, too. Reciting what has become the house credo, he goes, "We like to put a lot on one plate. Rather than a tiny bit on 10 plates."

Fresh fish is Bunnell's passion. He has befriended a number of suppliers, including a retired shrimper in Ketchikan, Alaska. Says Bunnell: "I'll get a call and he'll say, 'I'm pulling up my pots. They'll be on the plane this afternoon.' I'm his only customer. They're (the prawns) an absolutely beautiful product. It's been swimming the day I pick them up."

At least once a month the phone rings. And Bunnell hurries out to the airport to retrieve his shipment of prawns, which varies from 15 to 25 pounds. Bunnell generously shares the bounty with his good pal, Rick Mahan, who owns the Waterboy.

"I'm certainly not the cook that he is," an admiring Bunnell says of Mahan. "I'm in a different league. I'm not doing sweetbreads here. And I doubt that people who come in here even know what sweetbreads are. As much as I admire that style of cooking, I don't have that audience. We try to stay in our niche."

That said, Bunnell, who never had formal culinary training, believes he does share something in common with the accomplished Mahan.

"We're both hands-on owners," Bunnell says. "We like to see everything that comes out of our kitchens."

Education and opportunity

Jamie Bunnell grew up in Land Park. His father became a co-owner of Vic's Ice Cream, which was started by Vic Zito and Ashley Rutledge in 1947. Jim Bunnell was a master ice cream maker.

"I used to go to work with him when I was 5 years old," Bunnell says. "My father taught me to remember peoples' names. I think that's important. What I really try to create here is a sense of family."

Bunnell worked his entire boyhood at Vic's and never had a problem getting a date. Upon graduation from C.K. McClatchy High School, he left to test his wings. In short order, he tended bar at the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs, Colo.,; was the kitchen manager at the old Nut Tree in Vacaville; and worked himself up to become general manager at Flaherty's Oyster Bar in Carmel, where he really developed a nose for fresh fish.

By 1986, Bill Shanley had opened a second, bigger location of Shanley's Bar and Grill at 51st and Folsom. The small Broadway shop was expendable. Bunnell, eager to own his own place, scraped together $100,000 and bought the license and good will. He was 27.

"A lot of people didn't take me seriously," he says of those early days and long nights. "I was 25 years younger than a lot of my customers. It took a while for them to trust me."

Sticking to basics

Twenty years later, Bunnell is still 25 years younger than a lot of his customers. But he has learned a lot about the business, about food and value, about taking care of customers, about rewarding staff.

"It's one of my favorite places," says local attorney Doug McGilvray, 67, who, like many of the regulars, grew up in nearby Land Park. "You can always walk in there and find someone you know, someone you can talk to at the bar. Just wonderful food."

"I knew Jamie when he was a kid," says real estate agent Mike Puente, 64, a local gadabout, a longtime patron. "I may be prejudiced, but, in my estimation, it's the best food in town. Certainly the best seafood."

Lunch is gangbusters. Dinner (Monday through Friday), is less crowded. But the food-bar tally is a 70-30 ratio. Bunnell says he has no interest in lowering the demographic, or any plans to boost sales with a DJ or forays into minimal, New American cuisine. His metier remains fish and steaks.

But the lower Broadway locale, especially at night, when Jamie's takes on the visage of a haunted house, remains an obstacle.

"It's been a constant struggle," Bunnell says. "If we were further up the street, it would be better. So, we're definitely a destination place. You have to want to come here."

A dedicated staff

On another morning, Jamie's is slowly coming to life. Staff members are folding napkins at the bar. Jamie's wife, Vicki, runs the front of the house, and she's chalking today's specials: fresh wild salmon ($17.95), fresh blackened grouper ($16.95), fresh Dungeness crab leg Louie ($19.95) and smoked prime rib ($20.95).

The regular menu also offers an array of burgers, sandwiches, soups and salads.

Vicki Bunnell, 56, is the daughter of Andy Domich. She grew up flipping burgers at her dad's string of car wash-coffee shops. Christe Dantche, 32, has been bar manager for a dozen years. Evening chef Kevin Dich, 37, has been with Bunnell, off and on, since he was a student in high school.

Bunnell's right-hand man is a woman. Cindy Boc, 49, is an experienced chef who can cook anything. Dich is her brother-in-law. Both Boc and Dich are ethnic Chinese refugees from Vietnam. Incredibly hardworking, each has a second job apart from Jamie's.

The other staff member, dearly missed, is Jim Bunnell, who, after finishing his shift at Vic's, would hurry over to Broadway, transforming himself into a suave host. Jim Bunnell died in 1995, at age 63. But the old man's inimitable way lives on in his son.

Bunnell jams a visitor into the kitchen, where three's a crowd, and then heads out back to show off his pride and joy -- his barbecue. Bunnell has the only smoker in town created by acclaimed sculptor Gerald Walburg. In fact, no slight to "Indo Arch," but the steel smoker may be Walburg's greatest work of art.

Walburg is a longtime customer of both Jamie's and the Waterboy, whose metal sign out front he also designed.

"The main thing, I think, is that they're both good chefs and they use the very best ingredients," says Walburg, asked to compare Bunnell and Mahan.

Walburg's smoker is a mighty furnace. Bunnell cooks everything in it, from brisket to pork ribs, chicken to hot links. Just minutes ago, he removed three slabs of prime rib, each weighing about 12 pounds. A little after 11 a.m. now, they have been basking in the smoker since 5:30 a.m. Each slab has a patinated char, a luscious pink interior. Lunch, anyone?

Dreams and happy reality

Jamie's Bar & Grill is Jamie's Bunnell's life. He works seven days a week. On Saturdays, he prepares his roasts and turkeys; come Sunday mornings, he's the early bird at the farmers certified market, where Bunnell has cultivated a preferred crop of growers.

He has no plans to expand Jamie's Bar & Grill, or refurbish the building, which he doesn't own. Not that he doesn't harbor dreams.

"I would love to open up an oyster bar in town," he says. "Maybe combine it with a seafood market."

It's easy to imagine Bunnell as a fishmonger, in rubber boots and gutty apron.

He gets a dreamy, faraway look in his eyes.

"This is probably my life," he says, his gaze returned to plain-Jane Jamie's. "I'm married to this place. But I knew that when I bought it. I knew I was buying a job, and that I would never be an entrepreneur who would open up six more locations.

"But I want to be here. I couldn't be happier. I look forward to coming to work each morning. I love the people I work with. It's a great crew. They are part of my family. And I'm proud of what I'm putting out. We do things my way. I like it like that."

—Bob Sylva, Bee Staff Writer

Back to Press listings